STORIES

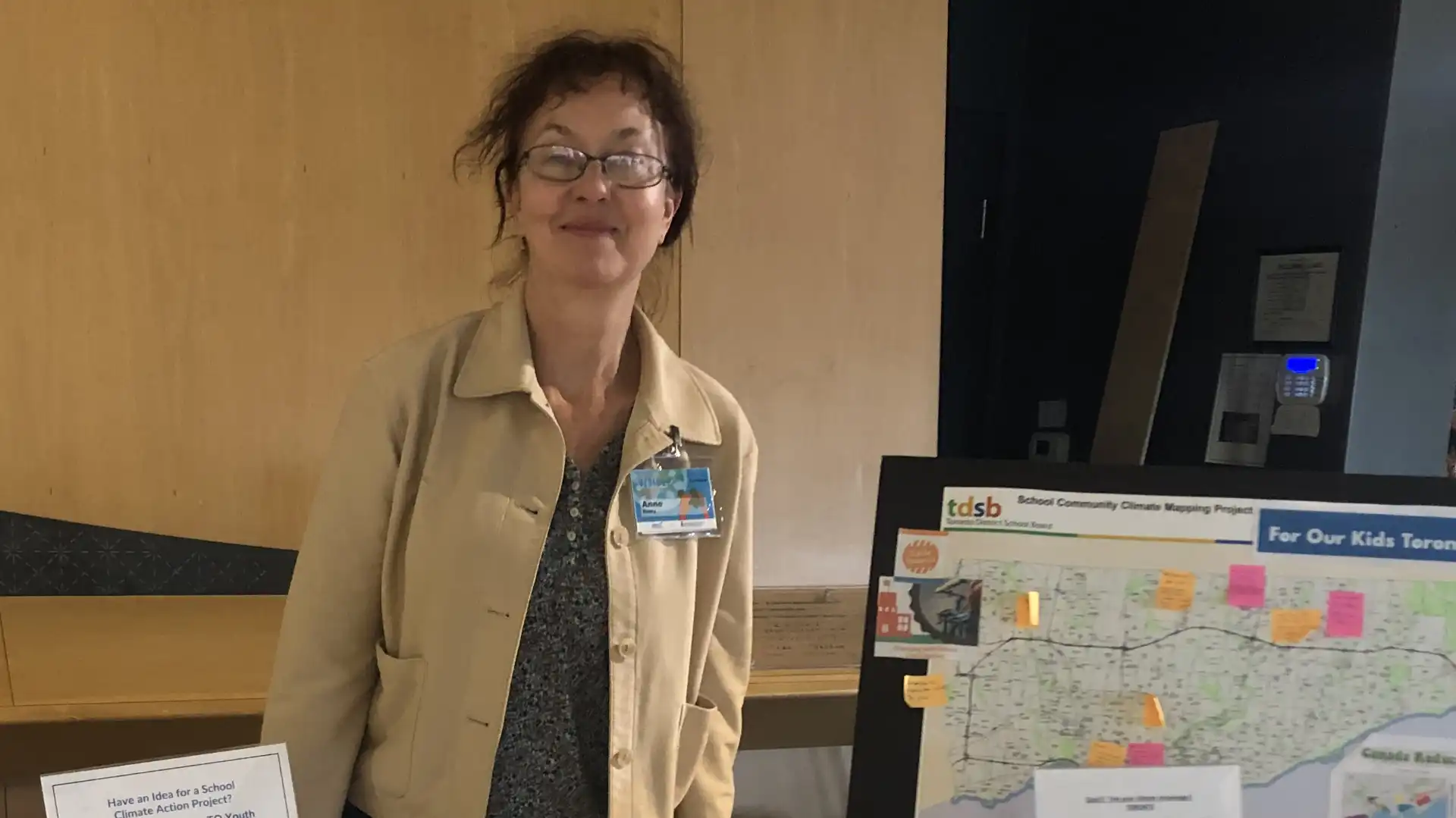

Anne Keary:

Building bridges between school communities and Toronto’s climate action plan

Anne is a parent, historian, independent scholar, and co-chair of the Toronto Climate Action Network, an umbrella organization of 74 member groups. She is a key organizer with For Our Kids Toronto, a group of parents and caregivers who advocate for climate justice. Anne is using these networks to help schools engage with Toronto’s ambitious climate action plan through diverse climate conversations in school communities. As part of her 2024-25 Parent Climate Fellowship, Anne co-authored a report, released in February 2025, on the fossil fuel industry’s extensive involvement in environmental and climate change education. Anne lives in Toronto with her husband and their two children attend college. She recently accepted the position of Regional Coordinator for Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment which advocates on the interconnected issues of climate change, justice, and health, including children’s health.

I’m originally from Australia and remember bad bushfires as a child, especially because my father worked in the volunteer fire brigades. During one fire he fought, I was terrified because ashes and blackened leaves were blowing around our house, and I could smell the smoke. He was fine, but it’s a visceral memory I’m returned to whenever I experience or read now about fires, especially since they’ve become much more intense.

My early life prepared me for climate justice activism. My mother, a biology teacher, shaped my understanding of environmental issues, and in college I was influenced politically by rallies against South Africa’s racist apartheid system. I studied history both as an undergraduate and then in graduate school, and this deepened my understanding of the colonial roots of systems of oppression and Indigenous Peoples’ efforts to defend their lands and cultures.

When the IPCC report was released in 2018, my daughter, then age 10 said, “Mommy, we have to do something big on climate!” Her sense that leaders were failing her propelled me to show my children that adults care and can be agents for positive change. I threw myself into supporting students in the first Fridays for Future Toronto climate strike. I was a complete novice but organized alongside other parents and youth. We pulled it off, which was energizing.

I realized that the climate wasn’t being addressed in schools, and that climate activists largely — and surprisingly — were ignoring the field of education. That propelled me to advocate for climate action within school systems through Toronto’s chapter of For Our Kids, a national parent-focused climate group. I and other adults also continued supporting student strikers and in 2019, they mobilized 60,000 – 100,000 people onto Toronto’s streets. It was massive, in part because a group of us parents asked the school board not to penalize striking students, and the board agreed.

There were two powerful outcomes of those strikes. First, the city of Toronto dramatically increased the ambition of its climate action plan. Second, it declared a climate emergency, which was endorsed by the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), one of the largest districts in North America. Further – and partly in response to parent advocacy – the City formalized a partnership with the school board to advance community climate action. The City established a grant program for youth-led school projects and the TDSB released a student climate action guide.

What strikes me as an historian is that when cities present their climate plans, it’s as if they always had these goals. The story of climate activism disappears, just as the activism of the labor or women’s suffrage movements was erased once the changes they fought for became institutionalized. Young people need those stories. There’s such pressure on them to be the climate activist, save the day, but imagine how powerful it would be for them if they understood that they’re standing on the shoulders of giants, that elders have been doing this work, seen big changes, and are ready to support them. That piece is crucial for building intergenerational ties.

Climate impacts are worsening here in Toronto. Heat waves are longer. Schools are hotter but lack air conditioning, which creates health problems for students, teachers, and staff. Downpours are more dramatic and will lead to mold in schools causing more illnesses. Toronto recently had the third 100-year flood in 10 years. We just don’t have the infrastructure for the weather we’re getting now. We’ve had so much stormwater flooding sewage treatment plants that the City has released raw sewage into Lake Ontario. It’s shocking.

It’s also intense for parents watching these crises multiply to think about the losses our children will face. It’s a visceral thing, our hopes for our kids’ futures. The good news is that most adults really do care about children. Potential Energy’s 2023 study found that the climate messages that resonate most with adults across 23 different countries are those that advocate “protecting the planet for future generations.”

Parents can express this message powerfully. At a recent public hearing in Toronto, action on the climate crisis was among the top issues addressed. The media featured parents speaking passionately about what this crisis means for kids and how they want a healthy, sustainable city for their children. Everybody wants a healthy future with better transit, green jobs, affordable green housing, more trees, and clean air, and one way to expand the climate bubble is to talk about those things. Toronto’s climate action plan invites people into that conversation.

A related aspect of my intergenerational climate justice work is supporting the youth climate lawsuit that includes my 17-year-old daughter. The seven plaintiffs, including three Indigenous youth, introduced expert testimony about climate impacts in Ontario, particularly on young people and Indigenous communities. The judge agreed with the facts but rejected the legal arguments. On appeal, the youth plaintiffs won a landmark ruling in 2024 affirming that Ontario’s weak climate targets risk the lives and well-being of Ontarians. I’m proud of her and her ongoing activism and loved organizing with her for last summer’s Global March Against Fossil Fuels.

I’ve recently co-authored the report Polluting the Schools: The Influence of Fossil Fuels on K–12 Education in Canada. It examines the involvement of at least 39 oil and gas companies and 12 industry-tied organizations in schools and climate-related education across the country and outlines their strategies. One of our key findings was that organizations that received funding from the oil and gas industry tend to obfuscate the role of the industry in driving climate change, greenwash the industry’s operations, and omit any mention of the urgent need to transition away from fossil fuels. Their involvement in educating children about the climate crisis is a conflict of interest that needs to be addressed soon, given the ever-increasing frequency of climate disasters here and around the world.

Our report also documents the antidote to industry’s actions. I see the potential for school board municipal government partnerships to keep climate change education in the public sphere, free from corporate influence. And cities are ideal for advocacy and civic engagement work in our neighborhoods and communities, developing elements of our city’s climate action plan.

We have an opportunity to think about our schools as community resilience hubs, and for parents to be involved in that kind of community-building at this time of increasing precarity. Many teachers want to do more climate change and climate justice education. Many students are interested in advocacy. We can help parents become allies to teachers and students by advocating in schools. I’m thrilled that in Toronto we’ve been able to start building those networks. It’s so important to demonstrate that kind of support for our children.