STORIES

Lisa María Madera:

Restoring rivers, weaving community, and connecting to Mother Earth through ancestral traditions in Ecuador

Lisa María is a mother, writer, and educator who serves as community weaver and riverkeeper for the Colectivo Rescate del Rio San Pedro, a group that creates intergenerational mingas to heal the San Pedro River in Quito, Ecuador. Made famous by the Inca, mingas, or minkas in Kichwa, bring together community members for shared projects, in this case to clean and restore the river while co-creating an educational and artistic experience. Over the past two years, the collective has hosted 20 mingas, harnessing over 8500+ volunteer hours to remove over 14 tons of debris from the river. Lisa Maria is a 2024 Parent Climate Fellow and the Director of the Minga Mundial Foundation which invites community members worldwide to join in global earthkeeping events.

I was born in Quito, Ecuador, in the middle of the world on the flanks of the volcano Pichincha. I’m the youngest of five. My family moved from the US to Ecuador in 1960 for my father, a doctor, to serve as a medical missionary. We lived in Quito, where I live now, for most of my childhood, but from age six to ten, I lived with my family in the Amazon in a military town called Shell Mera, named after Royal Dutch Shell which had founded it for oil exploration.

My mother started a school in Shell before I was born, a wonderful learning space with its back to the forest in one of the most biodiverse places on earth. Learning to think and feel in a world of such intense biodiversity made me keenly aware. I always felt the earth as a living, thinking being around me, caring for me. Most of the Amazonian rivers I learned to swim and think in were clean but are now poisoned. The forest of my childhood, where I learned to observe and ask questions, was a primary growth forest and now is mostly cut down. My generation has witnessed the devastating deforestation and plastification of our planet. I stand witness to the ecocide of the Amazon.

I constantly navigate despair because of the ecological genocide we participate in. I grieve our poisoned rivers and lost trees. I mourn our melting glaciers. I’m deeply concerned for my kids’ futures. Climate change has made Quito hotter and the weather has become erratic. We have water shortages and invasive plants. We’re at risk for floods, deadly landslides, and droughts, and like many countries, political instability makes us more vulnerable during climate-driven disasters. We’re also an oil and mining country and just signed a multibillion-dollar mining deal with Canada.

I think a lot about the transformative potential of collective action. In May, 2021, I was invited to join a minga to care for the San Pedro River, which is choked with plastic, textiles, sewage, and toxic chemicals. It’s the first river I remember meeting as a child and the first river my daughter met. A minga, or minka in Kichwa, is an ancestral tradition used throughout the Andes and Amazon, often for earthkeeping, farming, irrigation, or home-building. It’s a common form of reciprocal exchange that cares for the earth while building a community’s knowledge, connections, and sense of empowerment.

I found the mingas inspiring and surprisingly fun. You come together with old and new friends to care for the river, remove all this trash, then categorize and measure it. All ages from toddlers to older people are there hanging out by the river, learning, and having a good time. Afterwards we have our pambamesa, a shared meal, and celebrate a ritual together connecting to each other and our river. People tell us they find the mingas healing and feel better after participating. I’ve gone feeling sad and exhausted and returned regenerated, and watched my daughter and son do the same.

Our Colectivo is made up of individuals, families, and different allied organizations that share a simple mission: We want to swim in our river. In Ecuador we understand that our rivers are alive and have rights. It’s not just about cleaning the river, but also about changing our relationship to the river and to nature. We co-create a multi-disciplinary, educational, and intergenerational learning space where we work to restore the river and its ecosystems, connecting in multiple ways with the living earth. The motto of our Colectivo Rescate del Rio San Pedro is “The river called us. The river united us.” We listen together to the river and learn alongside artists and academics who teach us about the biodiversity of rivers, their ecosystems and water cycles, or about invasive plants or the false coral snakes and frogs living there. We’ve added birding to our mingas to help us listen and understand birds’ roles within our ecosystem.

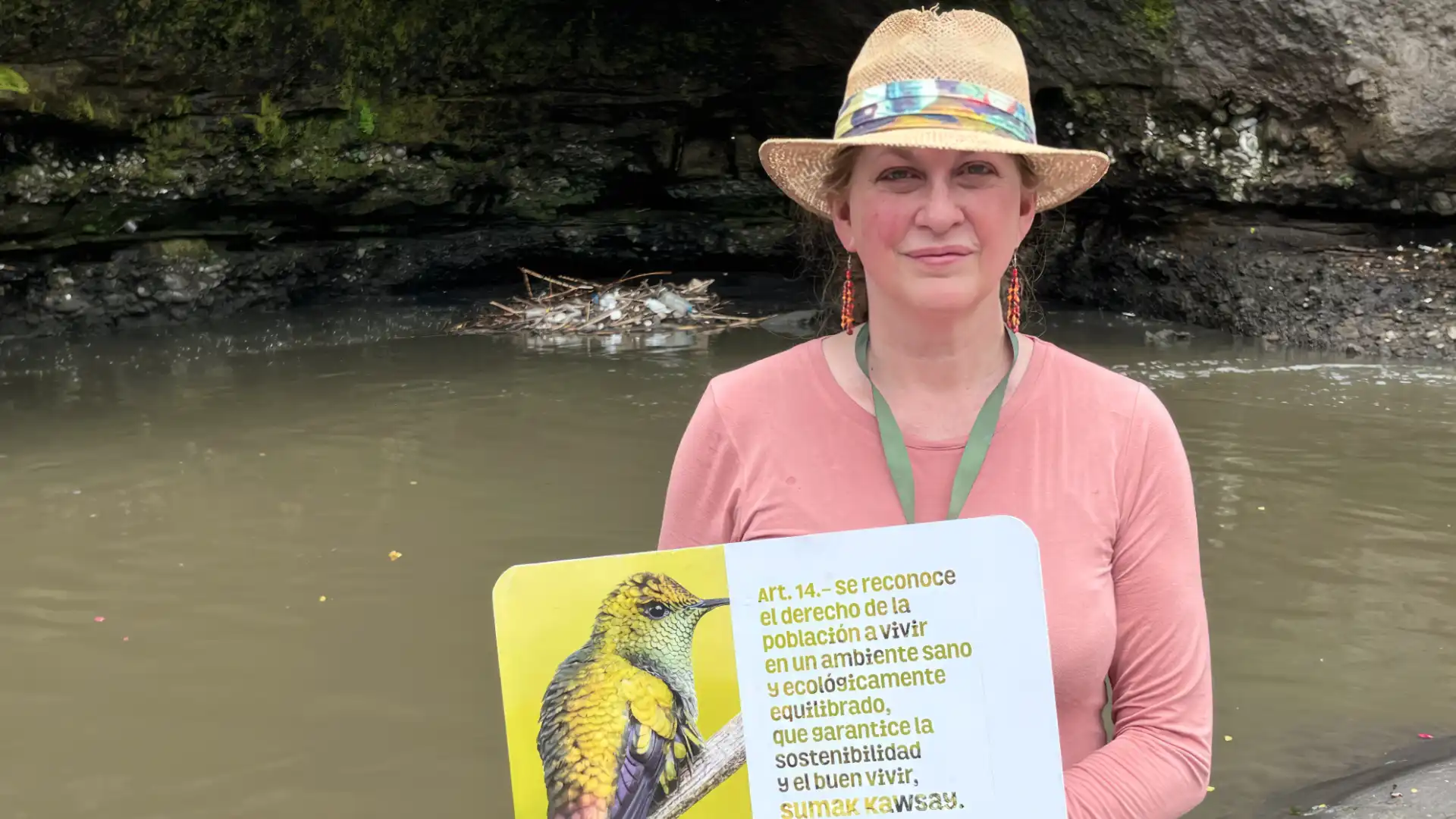

People in Ecuador strongly support the protection of rivers. We were the first country to declare the rights of nature in our constitution, and many battles now focus on the rights of rivers. Last year, Ecuadorians voted to protect the Yasuní National Reserve in the Amazon from oil extraction and rivers near Quito from mining. In January of 2022, courts ruled that Quito is infringing on the rights of the Monjas River and must restore the river. We sit on the governing body that helps implement that ruling. In May we supported collective legal action on behalf of the Machángara River’s rights, and in July 2024, the court ruled in the river’s favor, declaring the Machángara as a subject whose rights have been violated by the city of Quito.

To scale our riverkeeping model, we organized mingas for World Water Day 2023 in seven provinces in Ecuador and in seven Latin American countries. Together, with allies, we’ve engaged about 4,000 kids. To celebrate Earth Day 2024, we organized our first Minga Mundial para el Agua, meaning world water minga, on five continents. The Minga Mundial Foundation, which I direct, is a new international expression of our collective.

I’m interested in weaving intergenerational communities, fortifying our communal connections to nature, because I believe answers lie in the collective, synergistic knowledge passing through us at different life stages. A four-year-old’s questions are important to parents, grandparents, and other adults and children because they awaken awareness and help communities see differently. One way we include art in our mingas is by inviting children to draw, and they usually draw the river as clean. It’s interesting – and important– that they envision a whole, healthy river.

In the Andes, they say, “We feed the mountain and the mountain feeds us.” Our relationship is a relationship of kin. We care for Pacha Mama, our Mother Earth, and our Mother Earth cares for us. If that relationship goes awry, it becomes deadly and abusive: “We poison the river and the river poisons us. We devour the mountain and the mountain devours us.” It’s our responsibility as parents to teach this to our children. Our understanding of our responsibility to learn from and care for the living earth is something we pass down from generation to generation.

I believe we’re here to learn and teach, and through this process, we evolve. The minga has provided the richest educational space I’ve ever experienced. Mingas help communities reconnect to waterways as communal spaces and remind us that we’re part of a living, learning earth where our knowledge as a species is important. Our ability to tell stories that organize people is important. We need to weave learning communities of care and connection that wrap our whole earth.

We’re born to this time, to this place, and to each other. Together we know what to do.